Perfectly Depraved

The first of the five points of Calvinism is Total Depravity: as I understand it, the idea that on our own we can do no good, but that the good things we do are a result of God’s grace working through us. This leads to a troubling, ambiguous place: how should I feel about good works?

- Good Works are Good

- Good works are something to be proud of. I should try to be as good as possible, because faith without works is dead (James 2:17). Responding to God’s grace by loving others, not being jealous, greedy, lustful, mean-spirited, etc. is what God wants from us, and these good works are evident of God’s grace at work in us. So if I see other people being better Christians than me, I shouldn’t (of course) be jealous or envious of them, but I should be humbled by my lack of faith and see the error of my ways. It’s a clear sign that God’s grace is less active in me than in others. As I do more and more good things and less and less bad things (that is, as I become more and more sanctified), I am making greater and greater use of God’s grace and becoming a better Christian. This doesn’t affect my salvation, but it does affect my relationship with God.

- Good Works are Bad

- Good works distract us from God’s grace. People who are focused on good works forget that whether or not they do good works is unimportant – what is important is that God has saved them. In fact, as people do more and more good works, they need God less and less, and so God’s grace is becoming less active in their lives. The people who best exhibit God’s grace are the ones who constantly do bad things but also constantly seek forgiveness and repentance. This leads to a less careful and more active lifestyle, more willing to make mistakes and get into bad situations because it doesn’t affect salvation and creates needs (i.e., I need God to forgive me, I need God to be gracious enough to allow me to get out of this situation, I need a miracle to turn my life around), and the needs that are created give God more opportunities to work in clearer ways in our lives.

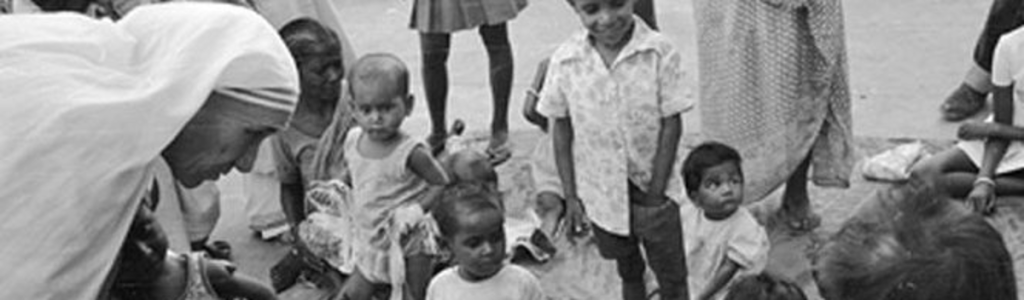

I tend to side with the “Good Works are Bad” side – if good works are good, then why did Jesus condemn the Pharisees? But what gets confusing, then, is that if I accept the premise that good works are “bad” (maybe that’s not the right word: a better word would be “distracting”), then the mistakes I make become “good” because they highlight God’s grace. And so this leads to a Pharisaical, holier-than-thou attitude towards sin and mistakes: if my life appears to be worse than yours, I’m a better Christian. The more good works you do, the less you trust in God. Mother Teresa, in this scenario, is a terrible Christian (at least on the surface) because she spent her life doing good things for people, living a puritanical life, and generally trying to get into heaven through good works. She didn’t give God enough opportunity to work through her because she was good enough on her own. (A study of her life will show that this isn’t true, but it is true of the generic public perception of her life as one completely dedicated to healing the untouchables and not seeking personal gain).

Paul did have something to say about this:

But law came in, with the result that the trespass multiplied; but where sin increased, grace abounded all the more, so that, just as sin exercised dominion in death, so grace might also exercise dominion through justification leading to eternal life through Jesus Christ our Lord. What then are we to say? Should we continue in sin in order that grace may abound? By no means! How can we who died to sin go on living in it? Do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? Therefore we have been buried with him by baptism into death, so that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, so we too might walk in newness of life.

Paul says that where sin increases, grace increases. So good works are bad, because they make less room for grace. So why not continue in a life of sin and mistakes, not worried about whether what we are doing is right? Because that is not what we’re called to do! Good works are evidence of faith, and they point to the grace present in Christ. Good works give the same amount of opportunity for grace to work in us as sin and mistakes do, especially if we take Calvin’s point that we can do nothing good on our own. Every forgiven sin and repentant sinner shows God’s grace, and every good deed done proves that God’s grace is at work. And, in the end, we have no control over the number or quality of good works that are possible for us: the progression of God’s sanctifying work in us is under God’s control (it in itself is an act of God’s grace), because it is God who gives the grace that makes good works possible. This doesn’t mean we should simply sit back and wait for good things to happen. The Westminster Confession of Faith says that our ability to do good works is not at all of ourselves, but wholly from the Spirit of Christ… but we shouldn’t be negligent as if we aren’t bound to do anything unless the Spirit moves us, but we ought to be diligent in stirring up the grace of God that is in us (PCUSA Book of Confessions 6.089). That same confession also says that sanctification is imperfect in this life; we can never completely get rid of sin, no matter how perfect we are, but that we still can become better and better Christians throughout our life.

With all this back and forth, it’s hard to decide what to do with my dissatisfaction that I’m not a better Christian than I am: is it right to be angry at God for not being more gracious to me (for not making me a better Christian)? Should I instead be angry with myself that I’m not “stirring up the grace of God” more than I am? Should I be thrilled every time I make a mistake? Should I be upset that I don’t make more mistakes? If you’re feeling the same sorts of things as me, maybe a better question to ask is this: Where does this guilt come from? Why do I feel a need to count my sins and determine where I stand? I don’t think this is how Jesus treats us, as lists of sins and graces. I like to think that he treats us as people who makes choices that at times reveal God’s grace in their goodness and at other times create opportunities for God’s grace to work through forgiveness and repentance. We aren’t asked to be perfect Christians, we aren’t even asked to constantly push ourselves to do more and more good works – we’re asked to love God and love our neighbors. We are asked, as Christians, to focus our actions and intentions on the present and the future, and not to dwell on the past except to learn. We don’t have to second guess whether we should be doing good or sinful things, we should only try to love God more. That’s a little less clear, and often translates to trying to do more good things, but here’s what’s really good about that: I don’t have to feel guilty about my mistakes or about how much I focus on doing the right thing. I just have to remind myself how much I love God for the grace I’ve experienced, whether I experience it in doing or receiving good works or whether I experience it in being forgiven for sins I don’t deserve to be forgiven for. I think God looks to the future with hope, not to the past with judgment – I think our memories are often much better than God’s. I’ll close with a cute parable that illustrates this:

Rumors spread that a certain Catholic woman was having visions of Jesus. The reports reached the archbishop. He decided to check her out. There is always a fine line between the authentic mystic and the lunatic fringe.“Is it true, m’am, that you have visions of Jesus?” asked the cleric.

“Yes,” the woman replied simply.

“Well, the next time you have a vision, I want you to ask Jesus to tell you the sins that I confessed in my last confession.”

The woman was stunned. “Did I hear you right, bishop? You actually want me to ask Jesus to tell me the sins of your past?”

“Exactly. Please call me if anything happens.”

Ten days later the woman notified her spiritual leader of a recent apparition. “Please come,” she said.

Within the hour the archbishop arrived. He trusted eye-to-eye contact. “You just told me on the telephone that you actually had a vision of Jesus. Did you do what I asked?”

“Yes, bishop, I asked Jesus to tell me the sins you confessed in your last confession.”

The bishop leaned forward with anticipation. His eyes narrowed. “What did Jesus say?”

She took his hand and gazed deep into his eyes. “Bishop,” she said, “these are his exact words — ‘I CAN’T REMEMBER.’”